Content warning: frank talk of suicide.

I think we all have a lot of formative moments in our lives. For me, it was stuff like coming out, the realization of my own mortality, the suicide attempt, and so on. I think that they tend to fall into two basic categories: those which affect us consciously, which we think about from day to day, with enough frequency to say ‘often’; and those which affect us more subconsciously, where we can go years or decades without really thinking about them, and yet they still inform so many of your actions.

Running away spent a lot of time in the subconscious camp, quietly informing several aspects of how I viewed myself and how I viewed the world around me. It was only recently, in the last year or so, that it’s come to the forefront, thanks largely to recent discussions with friends, family, and therapists. It’s only through that process that I’ve come to realize just how formative an event it really was.

In 1997, at eleven years old, I switched from living with my mom full time to living with my dad full time. My parents had divorced at some point early in my childhood, when I was too young to remember, and I grew up knowing nothing else.

The switch was part of a way to make sure that I grew up to be a balanced person. Having spent so much of my childhood in my mom’s household, it was time for me to spend more time with my dad than the schedule that we had maintained until then, Wednesday nights and every other weekend. The move was set for the time when I would be switching schools, anyway – I had just left fifth grade, and that was the time when middle school started in Boulder county.

I remember feeling a mix of excitement and apprehension as the date neared for the switch. On the one hand, it was exciting to be able to spend more time with my dad, who had always been keen on doing things with me that were fun. We’d go skiing, boating, spend a day trying to make the best paper airplanes, learn how to use the computer. On the other, though, I was apprehensive that I would be spending more time with my dad, who had always been somewhat distant, spending much of his time at the bar where my stepmother bartended, caring more about the grades that I brought home than my experience in school. In some senses, we were in line with each other and our expectations of what a parent-child relationship should be, and in others, we found ourselves at odds.

Even so, things wound up working out alright for sixth grade. I moved in with my dad, and moved to a new school. I had to spend one more year in elementary school, as Jefferson county didn’t start junior high until seventh grade, but it served me well. I wound up in a ‘gifted and talented’ program at the school due to how well I did at my previous school, and found the work to be both more engaging and more intense. My grades started to drop, I started to get bouts of depression and anxiety. At one point, I forged my parents’ signatures on my Friday Folder, which was supposed to be a weekly communication between my parents and my teacher, leading to a few weeks of being in trouble with both my dad and my mom.

Even so, although I was beginning to struggle for the first time in my life, I did my best to please my dad and maintain the enjoyable, if enigmatic, relationship that we had had up until then. I missed my mom, to be sure, having spent so much of my life until then living primarily with her, but I still felt like I could do well enough and excel in school living with my dad.

I don’t remember much about my summer between sixth and seventh grades, other than I had almost certainly gone back to the summer camp that I had gone to every summer before. I remember that this was the first time I started really enjoying writing. After leaving school for the summer, a friend and I had exchanged addresses and promised to write each other a letter over the summer. I don’t remember if we actually did, but those drafts of letters turned into my first attempt at journalling, which would lead me to writing stuff like this – putting my introspection down in words.

In the fall of 1998, I began seventh grade at junior high, one of those transitions where students go from being the oldest kids in school to the youngest. I figured that school would be similar, that it would be as though class had picked up where it had left off.

It didn’t.

Junior high and middle school is when they start introducing separate teachers for separate subjects, rather than a single teacher for core curriculum and separate teachers only for specialized subjects such as art, music, and physical education. This threw me for a loop, at first, and I wasn’t really sure why until I started digging back into my past over the last few years. What had started happening as puberty continued to roar through me is that depressive and anxious tendencies really started to take root. I would start fearing math class, rather than the subject of math with a familiar teacher, start worrying about the fact that band was mixed-grade and I would be pitted against eighth graders.

As a pre-teen, I had no idea what anxiety, panic, and depression were. I thought I was going crazy. My journals at the time were filled with fretting that I was having ‘psychotic episodes’ and wondering when these increasingly common attacks would become the new normal and coherent thought the brief rays of sunshine.

At the same time, I remember life getting harder for my dad. Things were happening at work – bad things – and while I can’t remember if it was that I had become more receptive to this or there had been actual changes, the perceived shift in my dad’s mood started to wear on me. Over the summer, he had announced that I was grown-up enough to stay home while he went to the bar for the evening. I’d get home at four or so, and dad would get home at nine or ten at night, having sussed out many of his problems of the day at work. I’d be in bed, or maybe we’d watch Deep Space Nine, and then we’d both go to bed.

In junior high, report cards came quarterly. My first one came sometime in October. It was not good.

My dad had become increasingly harsh on the topic of grades over the previous few weeks. Parent teacher conferences had not gone well at all, with my math teacher having particularly harsh things to say about me. I don’t even remember on what day of the week this happened, though I want to say Thursday. Dad came home for long enough to make us both dinner before he would head out to the bar. Although neither of us mentioned the fact that my poor grades were in my backpack, he must’ve known what the date had signified, as, before he left, he said something to the effect of, “When I get back home from seeing [your stepmom], you’ll show me your report card.”

I didn’t know what to do. Kill myself? I’d tried half-heartedly in the past. I collected the knife I’d stolen and kept in my desk. It was too dull. I had found a mirror from a makeup compact some days before, and I broke the glass, thinking I could use a piece of that instead, but couldn’t manage to get any of the shards of glass actually out of the compact, and as time drew on, I felt less and less like actually dying, as opposed to simply ceasing to be.

At this point, I need to take a step back. I want to avoid mixing the clinical with the reality, but I also don’t want to write the same story twice. > What was happening at this point, is that I was having an honest to goodness panic attack. To be specific, I was entering what is called a fugue state. I froze for several minutes, probably about an hour, sitting on my bed and holding a broken mirror in my hands. All thoughts had left me, and all I could think about was not being. Not being here, not being at all.

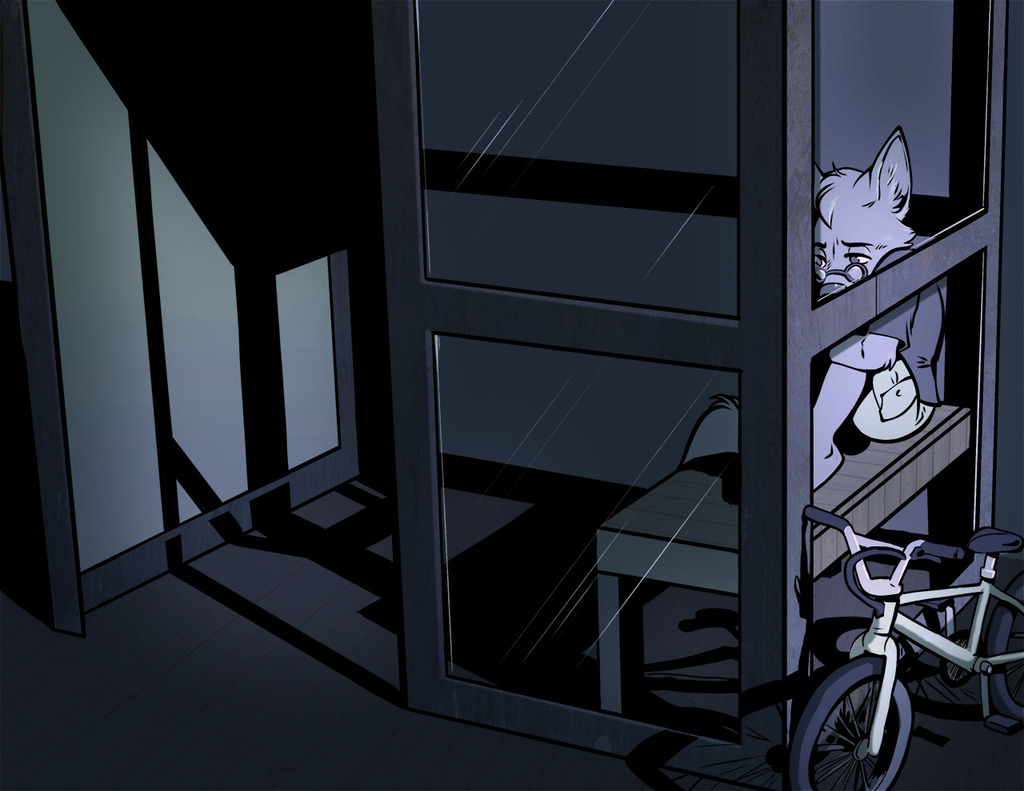

Having decided not to kill myself, I put on a hoodie, went up stairs and emptied the quarter jar of quarters, left the broken mirror on the counter, and grabbed my bike. I had no idea what I would do, where I would go. I just knew that I needed out of there. That place wasn’t a place I could be.

Still in a trance, I made my way to what I assumed would be a safe space to hide out for a while, long enough for my dad to not be out looking for me. I don’t know why that was something I was thinking of, but it was. I rode my bike to the nearby Wal-Mart, and hid behind it, where the semi trailers were parked. I hid between two storage containers in the back, the stars invisible to me due to the bright lights of the parking lot, and yet the shadows were such that I remained in total darkness.

I needed to get away. I needed to not be there. I didn’t have the language to explain panic, and I didn’t understand the importance of escape. What had happened, was that I had boundaries for what I felt were healthy means of interaction, and no means to communicate when they had been crossed. I had been slogging through anxiety with no way to explain to myself or others what anxiety was, and I had crossed the point where I could continue to exist in that state. The only solution was escape. Escaping into an internal world had worked until my dad demanded to see the report card, and escape by death hadn’t panned out. The only route left to me was literally escaping the situation.

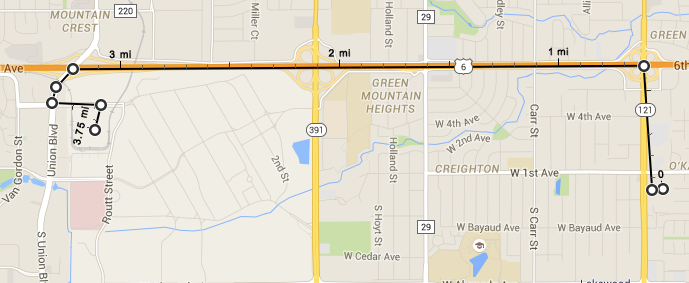

As the night wore on and the clock struck nine, I realized that I couldn’t stay behind the Wal-Mart forever. I’d need some place to go. With only my bike, my hoodie, and five dollars in quarters, I biked the four miles from where I had been camped to the nearest bus station serving the route that would take me back to Boulder. I had no plans beyond getting to Boulder, other than I figured I could be homeless there in relative safety.

As the night wore on and the clock struck nine, I realized that I couldn’t stay behind the Wal-Mart forever. I’d need some place to go. With only my bike, my hoodie, and five dollars in quarters, I biked the four miles from where I had been camped to the nearest bus station serving the route that would take me back to Boulder. I had no plans beyond getting to Boulder, other than I figured I could be homeless there in relative safety.

That’s where I spent the coldest night of my life.

The last bus to Boulder had already left, and so I was left on my own from about eleven that night until nearly six in the morning. I slept off and on on the bench in the bus-stop shelter. I hadn’t brought my bike lock with me, so I kept my bike leaning against the bench where I was dozing. I eventually got too paranoid and tied the sleeve of my hoodie around the top bar of the bike while I huddled deep within the relatively thin cotton of the jacket, no protection against the cold of the Colorado night.

At some point during the night, my anxiety abated enough to let me get some more perspective on the situation, and I started to think in terms of what I would do. I would take the bus to Boulder, get off near the then-open Crossroads Mall, and see if I could get something to eat. I never quite made it back to baseline in terms of anxiety, however. I was riding on a high, the fugue state constantly taking over and leaving me paralyzed for hours at a time.

The bus was warm. It had eaten $3.50 of my total of $5, but it was totally worth it. I fell asleep in the back seat within minutes of getting on, and was only awoken when the bus reached the end of the line and the kindly driver (who surely knew what was up) shook me awake and helped me onto my bike.

For lack of anything better to do, I rode my bike from the Walnut Street Station to my old elementary school. School wouldn’t be starting for another half hour or so, so I camped out in a playground near by, affectionately known as Rock Park. I sat atop the sculpture-cum-playground that made up the park’s central feature and watched elementary schoolers trudge toward their classes.

With a bit of rest under my belt and once more in familiar territory (literally three-quarters of a mile from my mom’s house, at the time), I was starting to come out of my state of panic. I was left with the dilemma of basically being a fugitive. I couldn’t go to my mom’s house, and I could never return to my dad’s. I was no longer anxious – my brain couldn’t hold that anymore – I was simply tired and sad.

Without anywhere to go or anything to do, I made my way back up to my original goal of Crossroads and puttered around the mall for a bit. My $1.50 wouldn’t buy me anything, so I just strolled around the bookstore for a while, always a favorite spot of mine. As I headed back out to where I’d left my bike in front of the entrance, I was startled by a red Honda Civic pulling up directly in front of me. My mom had found me. She admitted immediately that she had been canvasing the bookstores in town looking for me.

Even in my current state, I was a total dork.

The rest of that day and the next were a blur of crying. I was crying, my mom was crying…my dad may have been crying, but it wasn’t the type of thing I saw or heard from him. Mostly, he was angry.

I remember heated phone calls back and forth several times throughout the next few days. He had found my journal and accused me, “If you feel like you’re going crazy, maybe we should put you in the hospital. Is that what you want from us?”

I couldn’t answer.

“I’m throwing out a bunch of your stuff, since you don’t care about your place here.”

No answer.

“What’s with the broken mirror?”

No answer.

“What is it you want from me?”

I struggled for a way to put into words the anxiety, panic, and depression that had slowly taken over my life from the moment puberty had hit, exacerbated by the fact that I was living in a place where I felt distinctly unwelcome. I think I wound up mumbling something about the fact that, with my dad gone all evening at the bar, I had no contact with someone in utter control of my life other than through punishment. Even then, as a child, that only felt partly true.

The next few weeks were…odd.

At the time, I knew only that I was switching schools and moving back to Boulder in the process. I learned later – in 2014 – that my mom had taken control of the situation to have me move back to Boulder, and that, since then, my dad hasn’t talked with my mom except by necessity, such as my graduation and my wedding.

I eventually recovered, myself, although I would be plagued by anxiety and panic through the rest of that year.

I know now that I suffer from depression and generalized anxiety. Sure. That’s something that I have to live with. Coming to that admission to myself, though, was a process that took several years. It took me missing two weeks of class in college because I was terrified that walking behind anyone on a sidewalk would lead to a sexual harassment lawsuit. It took my boss telling me to go seek therapy, giving me a check for $1,000 in case I couldn’t afford it. It took a suicide attempt and leaving my job to work from home and burning a line on my forearm for every year that I’ve been alive.

I know now that I suffer from depression and generalized anxiety. Sure. That’s something that I have to live with. Coming to that admission to myself, though, was a process that took several years. It took me missing two weeks of class in college because I was terrified that walking behind anyone on a sidewalk would lead to a sexual harassment lawsuit. It took my boss telling me to go seek therapy, giving me a check for $1,000 in case I couldn’t afford it. It took a suicide attempt and leaving my job to work from home and burning a line on my forearm for every year that I’ve been alive.

I wrote this story because of how formative the act of running away has been in my life, but that’s not really what it’s about. As I was alluding to in the offset paragraphs above is that this isn’t about the act of running away, although that’s interesting in and of itself. This is about the ways in which anxiety controls life. This is about the ways in which panic takes over everything that you do. This is about accepting the idea that there’s only so much that you can take in life, and that the boundary isn’t hard and firm, and that figuring out when to take a step back, say “that’s enough”, and talk through the larger problem is a process that takes years and years and years, and that nearly two decades later, I still haven’t figured that out.

I still wind up in situations where I get stuck in a fugue state. I still find myself standing in the corner of a bookstore, feeling like I have no where to go, responding purely by rote memorization as I seek the nearest exit. Each of these situations has been preceded by a ramp up in anxiety and panic, and even though I’m getting better at setting boundaries for myself (I haven’t run away and I haven’t tried to kill myself, though I do still burn myself with some regularity), I’m still not there. I still find myself in those spots.

Ever since I graduated, my dad and I have had a better relationship. Actually, ever since I could legally drink, our relationship has been pretty cheery. I worry at times that my dad never wanted a kid, he wanted a buddy. A buddy he could share a beer with, someone he could commiserate about work-a-day life with. Maybe that’s true, to some extent. Even so, it feels good to be able to earnestly love my dad, even if it took a decade.

I never would’ve thought, but coming to terms with depression and anxiety has helped me grow closer to both of my parents. For that, I’m thankful. The road has, frankly, really sucked, but for that, I’m thankful.

Art by Mandi Tremblay.