I work for Canonical, Ltd, a company focused primarily on open source software, best known for their operating system, Ubuntu, a distribution of Linux focused on both the ease of desktop use, as well as a seamless experience across desktop, server, mobile, and TV. That’s not all that we make, though, and our umbrella of products and services stretches across several sectors of the software market.

I am on the Juju UI team. Juju is a dev-ops solution that allows packaging server software into Juju Charms, which act as biased installations of software that are built by people who know how that software can best be deployed. For instance, the Wordpress charm encapsulates an installation of Wordpress, just as the MySQL charm packages an installation of MySQL, such that, if you have a Juju environment up and running, you can simply run:

{% highlight bash %} juju deploy wordpress juju deploy mysql juju add-relation wordpress mysql juju expose wordpress {% endhighlight %}

and wind up with a proper installation of Wordpress talking to a proper installation of MySQL in the cloud of your choice.

I work on more than just the projects I have at Canonical, however. I’ve bought wholeheartedly into both the ethos and implementation of open source software, and so I work on releasing as much of my own free-time projects as open source as possible. Lately, the project that has been taking up much of my weekends and evenings has been an exploration of Go, a programming language by Google with a focus on simplicity and concurrency. I chose this language for this task because Juju itself, along with many of its tools, are written in Go.

The project I’ve been working on, Warren, is a pretty simple bit of web software that allows publishing of entities of various types - from blog posts to pictures and so on - and linking of those entities into a web of content. Or, rather, those are my hopes for it; it’s still in its early stages. I’ve learned a lot about Go, many Go web utilities such as Martini, Gin, and Gorilla, testing in Go using GoConvey, as well as the services that back Warren up such as Mongo and ElasticSearch.

Writing a web app such as this, it was a natural solution to charm Warren so that I could manage it, along with its backing services, in a scalable fashion on any of the clouds that Juju supports.

What I Did

The work that I’ve done to date consists of two parts beyond Warren itself: the Warren charm and the Warren bundle. Whereas charms describe the way in which a singal service is deployed, bundles are groups of charms that work together as a group of services providing a particular functionality. For instance, the Warren bundle includes Warren, Mongo, ElasticSearch, and haproxy for load balancing.

The Warren charm

I went with the idea of a “thin” charm. This means that the charm itself does not contain any of the source code or binaries required for building Warren itself. This is as opposed to “thick” (sometimes referred to as “fat”) charms, which contain a binary, a zip of source code, or some other means of deploying the service without reaching out to some external location. There are a few advantages and disadvantages to each:

Thin charms

- Advantages:

- Change to the code of the services does not mean change to the code of the charm.

- Charms are much smaller, and thus are uploaded to the environment fairly quickly.

- Disadvantages:

- Services will require access to wherever the source or binary to be deployed. In Warren, that’s the GitHub repository, but it may be a PPA or other source of packages. In some clouds, access such as this may be heavily restricted.

- Since the code must be fetched, potentially built, and then installed, some of the speed gains for not having to upload the charm are lost.

Thick charms

- Advantages:

- You can be guaranteed that the code that is in the charm is the only code that will be deployed in the service without having to use any work-arounds for pinning fetched source at a revision or tag.

- Deployment is usually fairly easy and fast, since you don’t have to worry about fetching source and building, and since no external sources are required, you can safely deploy behind a strict firewall.

- Disadvantages:

- Thick charms are rather large and may take a bit of time to actually deploy, since the charm will need to be uploaded to the environment either from your local machine or from the charmstore.

- Changes in your codebase will not show up when a new charm is deployed, since the code exists at one particular revision - this means that emergency bug fixes in your code mean an emergency charm release containing that fix, and a charm upgrade.

For Warren, I went with a thin charm for a few reasons:

- I live in the mountains, where Internet connectivity is limited to microwave line-of-sight of okay-but-not-great speeds. I didn’t want to have to re-upload the charm to EC2 every time I made a fix to it (charm developing being a particularly iterative process). Once the charm winds up in the store, should it wind up there, this will not be as much of a concern.

- I want to iterate fairly quickly on Warren, if it winds up going somewhere. I want to be able to iterate on Warren much more than I want to be able to iterate on the Warren charm, however, so I’d rather spend an initial investment allowing a means of upgrading the Warren source in a deployed instance of Warren through a configuration change (more on this later) than have a repeated time sink involved in building a new version of the charm.

In the end, the wins that thick charms get me are outweighed by the wins involved in thin charms.

The Warren bundle

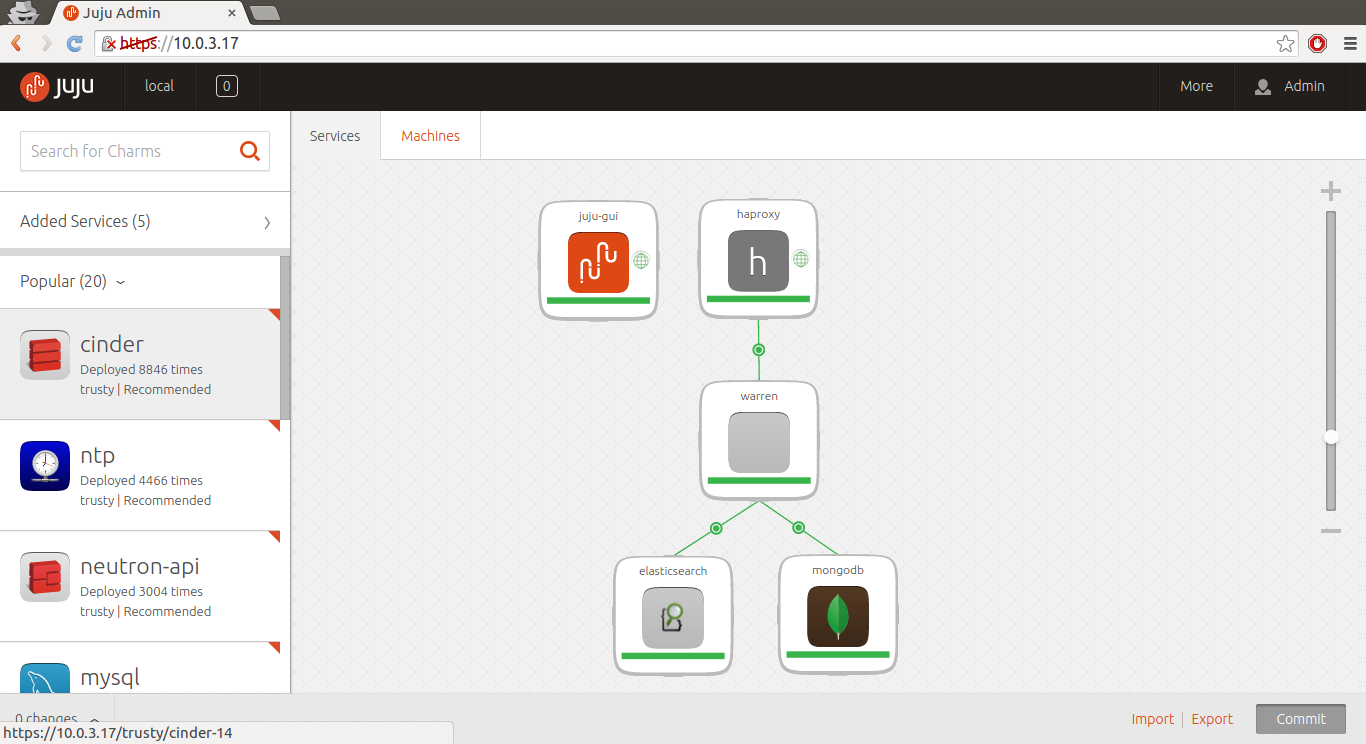

The Juju GUI is the project that I have spent the most time with during my time at Canonical. I started out on the GUI, and continue to contribute to it even as focus has shifted to other aspects of the various user interfaces to Juju. One of the things that I like about it is that it’s really easy to see just how your entire environment works and fits together. In the instance above, you can see haproxy exposed, which leads to Warren, which depends on Mongo and ElasticSearch. There’s a flow of traffic indicated in the diagram - a request to the exposed bit, which is proxied to Warren, which may make a request of either Mongo, ElasticSearch, or both.

Another benefit of the Juju GUI is that it allows you to export the current environment in the format of a Juju bundle, which is a repeatable representation of an environment. These bundles can then be reimported with the GUI or with another of our tools, Juju Quickstart, which allows building and managing Juju environments from the command line.

In this case, I created and exported my Warren bundle, but am not yet able to utilize it. This is because the Warren charm does not yet live in the Juju charmstore - it’s only deployed locally - and bundles do not support local charms yet. For now, though, I’m happy to have the bundle here as a reference to use when deploying Warren to a cloud.

The Good

My list of good things from this post will probably just read about the

advantages of using Juju. Once I had the charm up and running, it was

astoundingly easy to repeat the process: simply juju deploy

local:trusty/warren-charm from my charm repository. I have to say, there’s no

beating that. In the past, I’ve deployed and managed just about every one of my

projects by hand, and the lack of repeatability led to a ton of external cruft.

Deployment checklists, extended QA times, slower iterations, and so on. I think

that Juju helps alleviate all of these to some extent.

Additionally, in writing and testing the charm, I found all of the weak spots in my code that weren’t evident from a development environment. For instance, I had relied on several hacks and shortcuts supplied by the libraries I was using which, while they looked elegant, were not good solutions for a repeatable testing environment or a production environment. For instance, I relied on defaults for hosting static files and templates. While this made my code look clean and simple, it was not repeatable because there were no guarantees where those assets would be stored. Once I charmed Warren, that became evident, and I found ways to create a robust means of dealing with these problems that was both elegant, and non-magical.

The Bad

Docs.

I found the documentation around the python Charm Helpers, a package used for building and supporting charms, to be quite lacking. It feels as though new features were implemented in code while the documentation had not yet been fully written; what docs are there read as though the user should already understand how to use the package.

As a developer, I’m well aware of this pattern, and definitely guilty of it myself. Even so, I was left spinning my wheels for days as I tried to charm up Warren. I’ve helped with the charming of several different packages that we use within the company, but none of them use the new, undocumented features of charm helpers.

In the end, I wound up working off the old style of creating a python based charm - that is, rather than utilizing the service framework included with charm helpers, I created methods that were decorated as hooks, which were called simply whenever one of those hooks was fired. This is the style I’ve most commonly seen in the charms hosted in the charmstore, and while it does work, I get the impression that this newer services framework is much more elegant and easy to use. Easy to use once, that is, you understand how.

It just so happens, though, that the task that I’ve given myself over the next few months of free-project time at work is to help improve the documentation of the products and services that we have, whether that’s code-side in the form of docstrings, wider documentation included with the projects, tutorials, or videos. Indeed, that’s much of the purpose behind these dogfooding posts! So I’ll be working just has hard as the other teams, I hope, to help document Juju and how it can be used for managing cloud deployments.

What’s next

Next, I’d like to talk about more specifics about how the Warren charm works and the services with which it’s deployed. I hope to make this at least a short series, if not an account of my ongoing adventures with dogfooding Juju for my own purposes.